Her Secret Is Patience, Janet Echelman, Phoenix, Arizona

I returned from the SDA Conference in San Antonio over a week ago and I’m still synthesizing the information. No wonder, over the course of four days I attended presentations from fifteen artists and educators. I was inspired to try new things, to think deeply about why I make, and challenged to expand the scope of my work.

Janet Echelman’s talk, Taking Imagination Seriously, started the conference with her personal story of not only following inspiration, but the persistence and collaboration necessary to create her large-scale public art. (You can watch her TED talk of the same name here.) She emphasized how important it has been for her to treat each step of creating these enormous sculptures as a problem to be solved and not to back down when those problems seemed overwhelming. From mechanizing knotting techniques she learned from Indian fishermen, to developing software that can model how her sculpture will respond in a hurricane winds, to working with a conflicted City Council in Phoenix, she worked through each problem by asking questions and keeping at it until it was resolved. The audience was responsive to both the textile sensibility of her work and her lack of pretension, jumping to their feet at the end of her talk in a standing ovation. I get goose bumps even now thinking of the last words of her talk. When showing images of a project that is currently in process she said, “You can’t see this yet, it’s only an idea. But you will.”

I relate to this need for clarity and focus in my own work, to the state of holding an image in my mind until it is realized in its physical form. Making art is an act of faith. By holding tightly to the image of a finished piece, it can manifest into a physical object through persistence and hard work.

The most dynamic speaker at the conference was Otto von Busch. (Watch a you tube video called Hacking Design here.) His presentation, Interfaces of Fashion Activism, was a call to “Hacktivism,” rethinking the fashion industry through social activism. He proposes that fashion kills personality by proscribing what we wear and turning consumers into commodities. His work with students and designers uses craft as a tool for change through recycling and refashioning what we wear as an element of self-expression and as a way to create social bonds.

The most dynamic speaker at the conference was Otto von Busch. (Watch a you tube video called Hacking Design here.) His presentation, Interfaces of Fashion Activism, was a call to “Hacktivism,” rethinking the fashion industry through social activism. He proposes that fashion kills personality by proscribing what we wear and turning consumers into commodities. His work with students and designers uses craft as a tool for change through recycling and refashioning what we wear as an element of self-expression and as a way to create social bonds.

In a rush of words, Von Busch told of his many compelling projects including: Old is the New Black, in which people used black paint to transform stained garments at an event called Paint It Black; Neighborhoodies, a project in which students created garments in response to where they live and then were photographed while wearing them in their neighborhoods; and Community Repair, in which students bartered with others in their neighborhood to repair a garment and, in doing so, created a richer social fabric. “Mending is self-reliance,” he said when talking about Refuge in Restoration, a project at California College of the Arts where participants repaired garments by patching over worn places. Each patch was taken from the garment of another participant, thus creating a bond through both giving and receiving, mending both the social and physical fabric of their lives. More information on these and other exciting and inspiring projects can be found on his website, Self Passage.

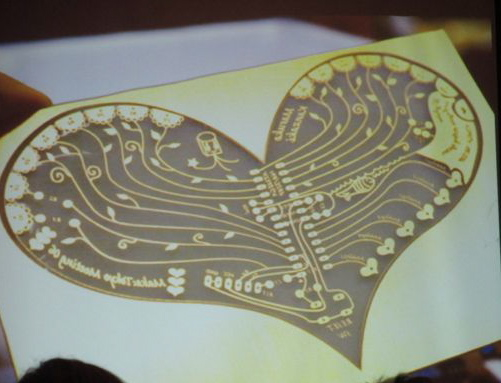

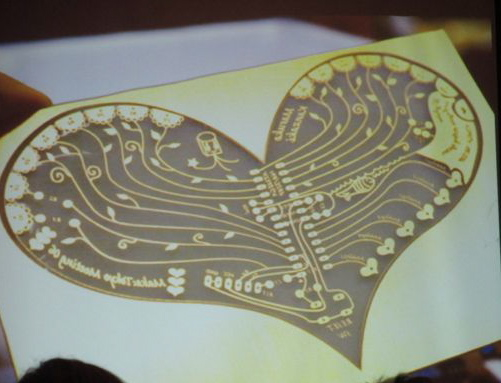

heart shaped circuit board from Lynne Bruning’s talk

Along with presentations by the Featured Speakers, there were smaller, concurrent sessions. Two talk I enjoyed were by Mo Kelman and Lynne Bruning. Mo Kelman’s talk, Skins and Skeletons: 3-D Textile Constructions, was a interesting and deeply researched survey of textile construction techniques across genres from Japanese kites, through fiber art, and into architecture. Lynne Bruning’s irreverent and approachable style provided a welcome break from the seriousness of many of the presentations as she gave us a tour of circuits and electronics in Welcome to the eTextile Lounge.

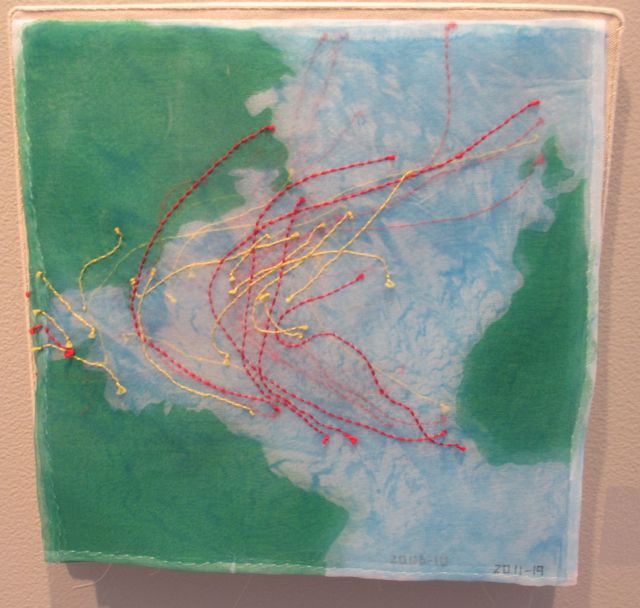

Changing Waters, Nathalie Miebach

The conference was closed by Nathalie Miebach‘s talk, Baskets, Graphs, and Numbers: Making Information Tactile. (Watch a TED talk by her here.) Miebach’s work uses basketry to create three-dimensional representations of weather data. I had seen images of her work but have always been distracted by the bright colors and swirling shapes and not sure how to interpret the data they represent. Her talk explained how she begins with a basic grid of reed that represents the 24 hours of the day and then builds the shape, adding different colors and weaves of reed to represent data such as temperature, wind speed, and ocean currents over time. The polymorphic shapes of the baskets are created by the data, not the whims of the sculptor, with sticks and spokes representing the phases of the moon, the height of waves, or the time of sunrise.

Miebach began her presentation by talking about the importance of play as a means of exploration and learning, citing research on early childhood development as well as her own experience. Play engages the imagination, not only in free-associative story-telling, but also through the proscribed rules of sports and games. I’ve found this to be true in my own work. Often, it is while working within limitations or “rules”, that my imagination is set free. I also related to Miebach’s statement that she “thinks with her hands.” I discovered in design school that I can’t think without a pencil in my hands. Miebach opined that because we now interact so much with computers, we are losing a kind of “tactile intelligence.” For millenia, we have learned through manipulating objects. How much are we losing by embracing the technical and limiting our experience with the physical?

tactile maps from Greenland

Miebach’s baskets are tactile maps of data. She explained how maps are structures for clarifying knowledge. She showed images of two historical tactile maps, one a stick map from the Marshall Islands and the other a map of the coast of Greenland. Both of these were “read” using touch, rather than the eyes. She also showed several maps of contemporary information, including a network of the internet. These new graphs show information interpreted in interwoven networks, rather like baskets. These networks more accurately describe concurrent information than the more traditional hierarchical forms of graphing information like the “family tree.”

Miebach explained that she creates tactile maps because, ultimately, our experience of weather is tactile. We can read the weather report, or watch graphs on the TV news, but our most literal understanding of weather is experiential. Miebach offhandedly pointed out that folklore is all about weather. Our childhood tales tell of desperate attempts to survive long winters, earthquakes, or epic floods. Extreme weather creates a sense of disorientation, of child-like fear of forces outside our control. Miebach’s colorful whirls and fanciful shapes give us information in a reimagined manner, much like the fairy tales of our youth taught us the rules for playing the game of life.

Changing Waters, detail

And as Miebach’s closing statement asks, “Where does the art begin and the science end?” Or conversely, where does the science end and the art begin?

Saturday was the 25th Annual Fremont Solstice Parade. I’m one of only seven people who has been involved in all 25, having gotten involved when I was just a youngster in my twenties. In the early years I was very active in both the organization and in making large-scale floats and costumes for the Parade. These days, I still wouldn’t miss it but I’m much less involved.

Saturday was the 25th Annual Fremont Solstice Parade. I’m one of only seven people who has been involved in all 25, having gotten involved when I was just a youngster in my twenties. In the early years I was very active in both the organization and in making large-scale floats and costumes for the Parade. These days, I still wouldn’t miss it but I’m much less involved.